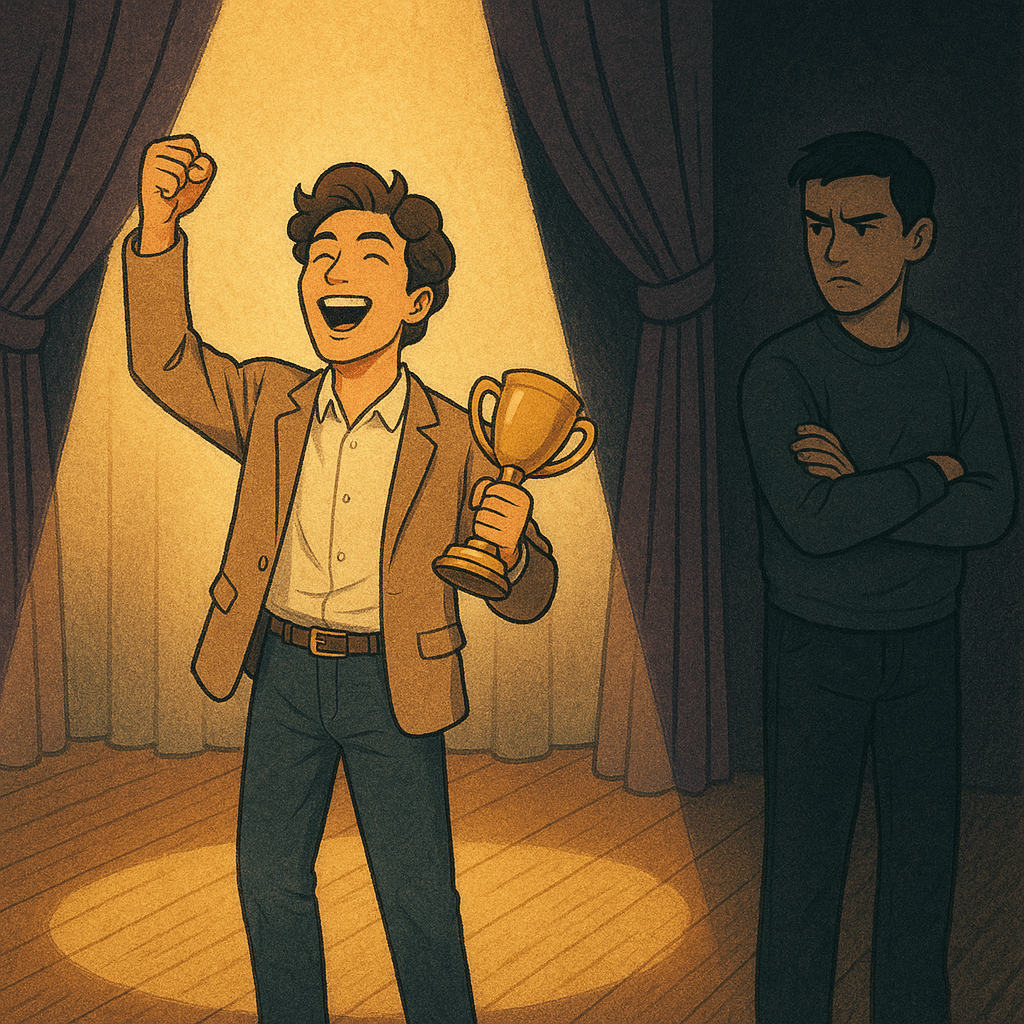

Envy is not just wanting what someone else has. According to psychoanalyst Melanie Klein, envy also involves a wish to destroy what the other person has. It isn’t only “I wish I had that,” but also “I wish you didn’t.” It carries a darker undertone. That’s why envy is rarely expressed openly in adulthood. Instead, it shows up as fake smiles, missed congratulations, or slowly fading friendships.

Recently, I noticed how muted people’s reactions were when someone in their circle achieved something significant. A major accomplishment was shared online, but the post stayed eerily quiet. Friends who’d known this person for years didn’t comment or congratulate them. The silence didn’t feel like apathy. It felt like emotional overload. As Adam Phillips says, envy is often triggered by people we compare ourselves to—not distant figures, but those closest to us.

According to Heinz Kohut, envy appears where self-esteem is fragile. Someone else’s success feels like our own failure. One person’s light casts another’s shadow. This is especially true among relatives, close friends, or people who started their journeys from similar places. When one rises, the other may feel left behind.

Clients in therapy rarely use the word “envy” directly. But they’ll say things like:

“I congratulated them, but it stung a little.”

“I don’t feel as close to them anymore.”

“I don’t know why, but I feel some distance.”

These often point to an old wound of not being seen, a sense of being left behind, or an internalised comparison.

Psychoanalyst Jessica Benjamin says that healthy bonding depends on both people in a relationship being able to express their subjective experience. Unfortunately, in many relationships, this symmetry collapses. One person shines, the other falls silent. That silence can slowly grow into distance—and even rupture.

Envy is not a bad emotion. But when it is denied or unacknowledged, it can quietly poison a relationship. In therapy, however, envy can open a door. Because it tells us what we value, what we long for, and in which areas we want to be recognised. Envy, therefore, is not a feeling to be judged—but to be understood.

As in so many childhood stories, envy often arises in the struggle for love. “My sibling got more attention” can resurface years later at work or in friendships. The praise someone else receives may echo a voice inside us that was never heard as a child.

Maybe that’s why the most meaningful congratulations are the heartfelt ones. Sometimes a message, a look, or an honest sentence is enough:

“I celebrate your success. I wish I could be a successful musician/painter/scientist/writer/entrepreneur/astronaut like you. Even if I didn’t follow that path, I’m proud to have a friend/sibling/cousin like you who did.”

And perhaps the most mature form of love is being able to recognise your own vulnerability in the face of someone else’s success—yet still speak up, still offer congratulations, still share in their joy.

When we envy someone’s success, our hope should be to notice that feeling, regulate it, and better yet, grow from it.

Instead of staying silent in the face of a musician we envy, let’s celebrate them—and practise more ourselves.

Or that business venture you always dreamed of? Let your friend’s success inspire you, and take your own steps forward.

We—especially in Central and East Asian cultures—are descendants of those who grow through mutual support.

All for one, and one for all.

π